Publication history

Lost Horizon: Posters and pictures | Publications | Formats & Versions | Tibet

Lost Horizon was written in London eighteen years ago during the winter of 1932. That was a hard winter for the world - the lowest point, had we then known it, of the Depression, and already dark with the threat of war to come. About that time it probably began to dawn on civilized man that he lived in an age of recurrent and deepening crises; that military victories did not bring peace; that his world wars would have to be given numbers; and that nowhere on earth was there any place where the storm could be outridden. It was in this mood that I wrote Lost Horizon. And I enjoyed writing it as one may sometimes almost consciously enjoy a dream. I remember taking walks near my home and climbing the English hills with wild thoughts of Everest and Kanchenjunga. I remember hours in libraries reading tales and legends of the great missionary travellers who explored all Central Asia centuries ago. And I remember when people asked what I was doing those days? It was fun to answer that I was busy on a novel about Tibet, thus leading to the natural question: "Had I ever been there?" I hadn't, and still haven't, and the way things now look I don't suppose I ever shall. But when recently I saw the motion pictures that Lowell Thomas and his son took during their astonishing Tibetan trip a year ago, I had the curious feeling that I had seen that land before with my own eyes; that I had heard its voices and chants and trumpets, and had breathed the thin icy air of its mountain passes. And a further strange thing is that I once met another traveller from Tibet – a rather odd fellow he was - and he assured me that he had actually found the lost valley of Shangri-La that I wrote about - a haven of peace and beauty hidden amidst the highest peaks in the world, and that it was all pretty much as I had described it. Of course, I can hardly believe that! But I should like to - I should like to. (Hilton 1950)

Hilton was obviously intrigued by the concept, and reality, of Tibet: a land with a 'strange yet profound religion; harsh yet benign theocracy; splendid and archaic civilisation; impossible landscapes of mountains and deserts; rugged yet amiable people; frustrating and tormenting isolation; and position atop the highest mountains on the globe' (Bishop 1989). This fascination gave rise to a timeless literary work which captured some of the mystery and essence of Tibet prior to its tragic invasion by China in 1950, the exile of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and the physical destruction of much of its Buddhist cultural heritage during the Chinese Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s. Tibet remains a country under occupation by the Chinese, and whether Shangri-La still exists - either in reality or only in the mind - remains to be seen.

2. The story of a manuscript

The following account refers to the sale of one of the manuscript copies of Lost Horizon, as offered by an American rare book dealer in 2008 [Source: Lakin & Marley Rare Books]:

One of the most celebrated and best-loved novels of the 20th century, Lost Horizon in 1933 introduced “Shangri-La” to the English language and remains the 20th century’s most renowned fictional vision of modern utopia. Lost Horizon was typed by the author himself at his parents’ modest semi-detached home at Woodford Green, Essex in April of 1933 after an intensive six weeks of composition. [NB: Hilton has stated that the novel was actually written during the northern winter of 1932.] It was submitted to, and immediately accepted by, the London publishing house Macmillan sometime before 9 May 1933. Also in early May 1933, a successful arrangement was made by Macmillan for Lost Horizon to be published simultaneously in the United States on 26 September 1933 in association with Hilton’s already established New York publisher William Morrow. The corrected ribbon typescript of the final draft of the novel was sent to Macmillan and this, the corrected carbon copy [i.e. the manuscript offered for sale by Lakin & Marley in 2008], was sent to Morrow.

HILTON, JAMES (1900-1954). FINAL ANNOTATED DRAFT TYPESCRIPT OF LOST HORIZON, [Woodford Green, Essex, April 1933], 257pp., 4to (10 x 8 inches), 206 pages with authorial manuscript revisions, corrections, deletions, and insertions in black ink, 61 of which include textual changes present in the work’s first edition, the first leaf with the author’s initial working title, “Blue Moon,” in handwritten block letters and signed [“James Hilton”], followed by a typed but unnumbered half-title and prologue title, all other leaves hand-numbered at the top right corner as follows: 1-128, 128A, 128B, 129-206, 206A, 207-209, 209A, 210-211, 211A, 211B, 211C, 212-236, [a single page designated “237-242”], 243, 243A. [Unnumbered epilogue title page], 244-253. All leaves have four uniform holes in the left margin for insertion in a binder and are age-toned with occasional minor chipping; many have blue-pencil and ordinary-pencil corrections in two other distinct, certainly proof-corrector, hands (see below). The final three-and-one-half paragraphs of the epilogue (918 words) are not included with this typescript; this missing portion constitutes four typewritten pages at Hilton’s rate of roughly 215-230 words per typed page and may represent a final set of changes to the novel’s coda delivered later under separate cover. Otherwise the typescript is entirely complete and corresponds to the printed text of the first edition, with each leaf now placed in an archival Mylar sleeve and the entire manuscript housed in a new custom quarter-morocco slipcase. Provenance: “The Papers of James Hilton”, Christie’s Los Angeles, 18th November 1999 (lot 83).

There are some minor but fitfully significant textual differences between the first English edition and the first U.S. edition and these small differences exist entirely due to William Morrow’s last-minute efforts to provide the novel with “Americanization” for its readership. Upon receipt of the present typescript in New York, Morrow put its blue pencil to work. The alterations made by this corrector can be found most prominently in the improvement of those speeches made by the one American character in Lost Horizon:Barnard, the disgraced post-1929 Wall Street Crash stock swindler on the run. In addition, Morrow’s corrector did a little translating for American readership (e.g. “petrol” became “gasoline,” “gramophone” became “phonograph”). Further, a dose of editorial polish was added to Barnard’s argot, as Hilton’s ear for American slang wasn’t completely true. It also appears, surprising as it might seem, that Hilton did not review the American galleys as every single one of Morrow’s blue-penciled changes, even those of slightly dubious value, seem to have made it into the first American edition. William Morrow’s revisions of the text had consequences for posterity. In 1939 the American text became the standard due to Lost Horizon’s publication that year as the historic first-ever American mass market paperback (Pocket Books #1) which was reprinted 105 times by the 1960s and translated into thirty-four other languages. By 1969, Pocket Books alone had sold two million copies around the world.

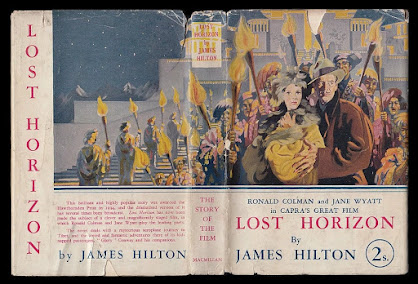

The adaptation of the 1933 novel into the 1937 film further enhanced Lost Horizon’s worldwide fame and the film has long been considered a cinematic classic. It received seven Oscar nominations (including Best Picture) and became the sixth highest grossing film of the 1930s. Its reputation, like the novel’s, continues to grow after almost 75 years. The making of the film can be credited to the unrelenting and inspired efforts of three-time Oscar winning director Frank Capra (“It’s a Wonderful Life” “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington,” “You Can’t Take It With You”) who fell in love with Lost Horizon after idly purchasing the novel for casual reading on a train. He noted in his autobiography that: “I read it; not only read it, but dreamed about it all night.” The film adaptation starred Ronald Colman in one of the many roles he seemed born to play and its much-lauded screenplay was written by Capra’s favorite Oscar-winning scribe, Robert Riskin who, in consultation with Hilton himself, wrote a script which was faithful to the dreamlike quality of the book. Riskin’s sensitive understanding of the novel can be heard in lines of dialogue such as one murmured by Sam Jaffe as the two-hundred-year old High Lama: “There are moments in every man’s life when he glimpses the eternal…” The fact that Frank Capra actually purchased the first heavily corrected draft of the manuscript itself directly from James Hilton (along with the film rights) in 1935 is not quite as odd as it might seem for two well-documented reasons. Capra was already in the process of building a remarkable literary library with the help of legendary rare book dealer Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach. And Capra shamelessly used his purchase of the manuscript as part of his publicity campaign to spur interest in the film. For example, Time magazine’s review of the film’s premiere in its 8 March 1937 issue stated that “Director Capra went to work with typical Hollywood opulence. He bought the original manuscript.”

In actual fact, Capra bought two manuscripts of Lost Horizon, first draft and final draft, both of which appeared together in Parke-Bernet’s April 1949 sale of Frank Capra’s library. The “first draft typescript,” as described in Parke-Bernet’s sale catalogue, consisted of 259 leaves. It had been typed rapidly without editing or pause as was consistent with Hilton’s working methods throughout the entire length of his prolific career. It was also typed on the versos of the original manuscript of Hilton’s earlier novel Terry which had been published in 1927, an odd frugality but not altogether surprising given that Hilton was still living and writing at his parents’ house during the time of Lost Horizon’s composition. Despite eight published novels, by 1933 he had achieved neither literary nor financial success. This “first draft typescript” was then revised via erasure, over-typing, and interlinear holograph additions. All these working methods are depicted in the Capra catalogue, in the plate reproduced opposite Lot 207’s printed, full-page, description. Along with the first draft in the Capra sale, there was a final draft typescript (the corrected ribbon copy) of Lost Horizon. Here follows an excerpted section from Parke-Bernet’s complete description in 1949:

[NB: This manuscript was subsequently sold by Bonhams, New York, in 2016]

| Year | Month | Description | Printing | |

| 1933 | September | Grosset & Dunlap, New York | 1 | Silver & red dustjacket |

| 1933 | September | Macmillan & Co., London. Octavo | 1 | Cream & brown dustjacket |

| 1933 | 27-Sep | William Morrow & Company, New York, 1st edition | 1 | Orange & yellow dustjacket |

| 1934 | May | William Morrow & Company, New York | 2 | Orange & yellow dustjacket |

| 1934 | September | William Morrow & Company, New York | 3 | Orange & yellow dustjacket |

| 1934 | September | Macmillan & Co., London | 4 | Cream & brown dustjacket |

| 1934 | October | Hawthornden Prize edition, Morrow, 1st printing | 1 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | October | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 2 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | October | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 3 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | October | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 4 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | November | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 5 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | November | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 6 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | December | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 7 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | December | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 8 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1934 | December | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 9 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1935 | February | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 10 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1935 | August | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 11 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1935 | September | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 12 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1935 | November | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 13 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1935 | December | William Morrow & Company, New York | 9 | Orange & yellow dustjacket |

| 1935 | ? | Macmillan & Co., London | Cream & brown dustjacket | |

| 1936 | January | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 14 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1936 | May | Hawthornden Prize Edition | 15 | Blue dustjacket |

| 1936 | August | Hawthornden Prize Edition, Grosset & Dunlap - endpapers with scene from film | 16 | Full colour dustjacket |

| 1936 | August | Hawthornden Prize Edition, Grosset & Dunlap - endpapers with scene from film | 17 | Full colour dustjacket |

| 1936 | August | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 1 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1936 | October | Hawthornden Prize Edition - issued as Author's Edition | 18 | Multicolour dustjacket |

| 1936 | October | Photoplay Edition, Cottage Library, Macmillan, 12mo | 1 | |

| 1936 | October | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 2 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1936 | November | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 3 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1936 | ? | Athenaeum, Budapest | 1 | |

| 1936 | ? | Author's Edition | 2 | Multicolour dustjacket |

| 1937 | May | Author's Edition | 4 | Multicolour dustjacket |

| 1937 | ? | Author's Edition | 5 | Multicolour dustjacket |

| 1937 | April | Photoplay edition | ||

| 1937 | September | Photoplay edition | ||

| 1937 | October | Photoplay edition | ||

| 1937 | ? | Photoplay edition | ||

| 1937 | March | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 4 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1938 | ? | Photoplay edition | ||

| 1938 | January | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 5 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1938 | March | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 6 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1938 | March | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 7 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1938 | March | Popular / Photoplay Edition, Grosset & Dunlap | 8 | Brown & red (photo) dustjacket |

| 1939 | May | Pocket Book Edition | 1 | |

| 1939 | June | Pocket Book Edition | 2 | |

| 1942 | ? | Pocket Book Edition | 21 | |

| 1943 | ? | Macmillan, Canada, 1st printing | 1 | |

| 1944 | ? | Macmillan & Co., London | Cream & brown dustjacket | |

| 1946 | ? | Macmillan & Co., London, 12mo | ||

| 1947 | ? | Pan Books | 1 | |

| 1948 | ? | Pan Books | 2 | |

| 1950 | ? | Pan Books | 3 | |

| 1953 | ? | Pan Books | 4 | |

| 1956 | ? | Pan Books | 5 | |

| 1957 | ? | Pan Books | 6 | |

| 1960 | ? | Pan Books | 7 | |

| 1966 | ? | Author's Edition | 24 | |

| 1969 | ? | Author's Edition | ||

| 1972 | ? | Pocket Book Edition | 72 | |

| 1975 | ? | Author's Edition | 30 | |

James Hilton's novel Lost Horizon was first published by Macmillan and Co., London, in September 1933. It was a hardback, octavo (8vo) edition bound in green or red cloth. The dust jacket bore a plain, pale cream background with black text and a brown drawing by 'KB' of lamasery buildings perched precariously on the side of a snow-covered mountainous landscape, representative of the artist's vision of the Tibetan Himalayas. In later printings the drawing was in blue on a white background.

William Morrow & Co. of New York, and its subsidiary Grosset and Dunlap, both issued the first American editions during 1933, with similar, though not identical, dust jackets. The first William Morrow edition bears a copyright date of 31 August 1933, marking its release at the same time as the British edition. It did not appear in the shops until a month later.

The Grosset and Dunlap edition of 1933 bears a different cover and dustjacket.

Lost Horizon was first published on both sides of the Atlantic in the autumn of 1933. Its sale was slow at first, and though it had a few fervent and even notable admirers, by Christmas of that year one might have prophesied that even the ripple it had stirred might already be stilled. As this happens to almost ninety nine percent of novels, I was not enormously surprised, though I was - dare I say it! - a little disappointed. But in June, 1934, the book received the Hawthornden Prize, which is given yearly in England for an imaginative work written by a British author under the age of forty-one. The result was in the nature of a resurrection; the sale of the original English edition began to gather momentum, while in America the publishers took the almost unique step of issuing the book afresh. Such a second chance was well taken, for during the past two years seventeen editions have been printed. This, the eighteenth, makes a permanent one. I recount these details without vainglory, though I cannot pretend to be indifferent over them. There is certainly no book of mine whose success I ever desired more keenly, for Lost Horizon was, in part, the expression of a mood for which I had always hoped to find sympathizers. I found them in the thousands, and now, through the medium of the screen version that Frank Capra has made, the same mood, I hope, will find them in the millions. Which leads me to the final remark about this mood. When Lost Horizon first appeared three years ago, its message of the peril of war to all we mean by the word "civilization" was considered topical. "It will be such a storm as the world has not seen before. There will be no safety by arms, no help from authority, no answer in science. It will rage till every flower of culture is trampled, and all human things are leveled in a vast chaos... The Dark Ages that are to come will cover the whole world in a single pall; there will be neither escape nor sanctuary, save such as are too secret to be found or too humble to be noticed...." How much happier one would be to dismiss all this as thoroughly out-of-date, than to admit, as one must, that in 1936 it has become more terrifyingly up-to-date than ever! James Hilton, London, August 4, 1936 (Hilton 1936)

By August 1936 Hollywood had also intervened to further promote the book. During 1934 movie director Frank Capra picked up a copy at a train station and upon reading it immediately determined to make a film version. By the middle of 1936 his production was well underway and its release eagerly anticipated due to an extensive pre-release publicity campaign. As a result, the 16th printing of August 1936 included end papers with a scene from the forthcoming Columbia Pictures adaptation. This was eventually released the following March. The dust jacket included artwork by famous American artist James Montgomery Flagg which would feature in posters and other promotional material for the film.

For a brief period during 1936 the Hawthornden Prize edition was published in the US as part of the Author's Edition, with the latter also serving as a film tie-in, though not in the traditional sense whereby numerous images from the film would be featured throughout. A confusing number of variants were therefore issued in the US during this period, usually under the imprint of both William Morrow and Grosset & Dunlap, and with differing dust jackets, cover illustrations, embossed detail and sizes.

A Grosset & Dunlap so-called Popular Edition appeared in eight printings in the US between August 1936 and March 1938, alongside the Author's Edition.

Foreign editions of Lost Horizon began to appear shortly after the initial UK and US releases, with the book ultimately translated into at least 34 different languages according to one source. For example, A kék hold völgye [Lost Horizon] was published by Athenaeum in Budapest during 1936.

This was the first of many subsequent editions in that country, including one by Bibliotheca in 1946. Numerous Spanish language editions were also published for the Mexican, South American and Spanish markets. Some of these are listed below. Most significantly, William Morrow & Co. issued a soft cover, paperback edition during May 1939 with a pictorial cover. This was the first for Lost Horizon and the initial issue of the new Pocket Books brand. It proved a huge success.

Also during World War II an illustrated version was issued by the World Publishing Company of Cleveland, Ohio, with drawings by Kurt Weiss. The status of this edition is unclear. A South American edition also appeared around this time.

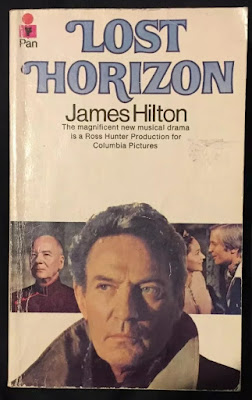

Macmillan in the UK first issued Lost Horizon as a paperback in 1947 as part of the Pan Books series. The war had put paid to an earlier release in that country due to paper rationing.

* Pan Books, Macmillan, circa 1948. 2nd printing.

* Pan Macmillan, UK, 1950. 3rd printing.

* Mexico, 1960s. Adaptation of the 1939 Pocket Books cover artwork.

* Great Pan, Macmillan, UK, 1960. 7th printing.

* Orizzonte Perduto, Mostra, Italy, 1960.

* Ediciones CP / Reno, Mexico, 1960, 1973.

The International Collectors Library in 1962 publish a James Hilton compendium edition in hardback form containing Lost Horizon and Goodbye Mr Chips, both of which had been popularised by Hollywood adaptations. Such editions would become common through to the 1990s. Frank Capra's Lost Horizon was also re-released in 1943, 1948 and 1956, keeping the story in the public eye, as did its screening on television from the late 1950s. Meanwhile, variants in publication format and cover design continued to appear through the 1960s.

* Reader's Enrichment Series, Washington Square Press, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1968.

* Orizzonti Perduti, Morbida, Italy, 1968.

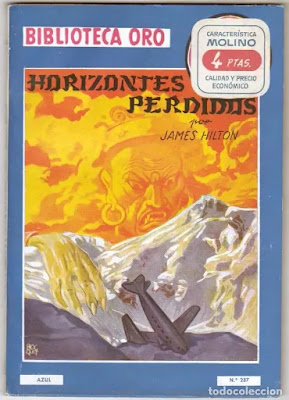

* Biblioteca Oro, Mexico, 1960s. Comic book version.

* Biblioteca Oro, Azul Molino no.287, Mexico, 1960s. Comic book version.

* National Classic Comics, National Bookstore Inc., Manila, 1960s, 40p. Art by Alfred C. Manuel. English edition. Also issued in Spanish.

* Macmillan's Stories to Remember series, UK, 1960s.

* Simon & Schuster, New York, 1973. Film tie-in.

* Kakugawashoten, Japan, 1973. Film tie-in.

* Lost Horizon, Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts / Pan Books, London, 1978.

* Dial Comics Group, US, 1970s. Comic book version. Relates the story to Marvel's Dr. Strange.

* Tabte Horisonter, Lindhardt Og Ringhof, Denmark, 1980s.

* Bortom Horisonten, Sweden, 1982.

* Pendulum Press, Contemporary Motivators series, US, 1982. Comic book version.

* Aims International Book Corporation, Italy, 1983.

Bonhams, An Annotated Final Draft Manuscript of Lost Horizon, Bonhams, New York, 30 November 2016. Available URL: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/23477/lot/542/?category=results.

Capra, Frank, The Name Above The Title, Macmillan, New York, 1971.

Carter, Erlet, The space of the dream: a case of mistaken identity? Area, 2001, 33(1), 47-54.

Chou, Shiuhhuah Serena, The Secret of Shangri-La: Agricultural Travels and the Rise of Organic Farming Discourse, Comparative Literature Studies, 50(1), 2013, 108-119.

Classen, Albrecht, Hermann Hesses Glasperlenspiel (1943) und James Hilton's Lost Horizon (1933): Intertextuelle Beziehungen zweier utopischer Entwurfe aus den Zwischenkriegsjahren, Studia Neophilologica: A Journal of Germanic and Romance Languages and Literature, 2000; 72 (2), 190-202.

Crittenden, Victor. Watkin Tench, La Perouse and Lost Horizon, Margin: Monash Australiana Research Group Informal Notes, 70, November 2006, 4-9.

Lakin and Marley, Featured Manuscript - Lost Horizon, Lakin & Marley Rare Books, San Francisco [webpage], 2008. Available URL: http://www.lakinandmarley.com/featuredmanuscript.html.

Mather, Jeffrey, Captivating Readers: Middlebrow Aesthetics and James Hilton's Lost Horizon, CEA Critic, 2017, 79(2), 231-243.

Musuzawa, T., From empire to utopia: the effacement of colonial markings in 'Lost Horizon' (James Hilton), Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, 1999, 7(2), 541-572.

Riskin, Robert, Six Screenplays, edited and introduced by Patrick Gilligan, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1997.

Wikipedia, Shangri-La [webpage], 2019. Available URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shangri-La.

Last updated: 8 July 2023

Michael Organ, Australia 🇦🇺

Comments

Post a Comment